Author, Speaker, Instructor, Radio Host

The Framers of the United States

Constitution purposely set up the federal government during the Philadelphia

Constitutional Convention to be a limited government, rather than a national

government. They also, knowing the

dangers of pure democracy, put into place checks and balances, and other

mechanisms, to ensure the system was a republic, rather than a pure

democracy. The States, whose delegates

at the Constitutional Convention were the architects of the new American

federal government, recognized the dangers of an all-powerful centralized

government with all powers consolidated under its umbrella, so they created a

limited government, a federal system with only authorities granted to it

necessary to carry out its tasks as the country's primary connection with the

rest of the world, and one that could act as a mediator between the States when

disputes were to arise. From the annals

of the Saxon system of government and the lessons garnered from the volatile

history of Israel in the Holy Bible, the Founding Fathers fashioned for the

first time in history a federal government with limited powers and a duty to

protect, promote, and preserve the Union of States. In short, the federal government was designed

to be a servant, not the master.

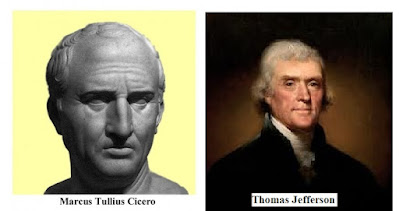

The constitutional delegates drew much of their research from history. In addition to British history, which was largely steeped in the influences of the Saxons and Angles, the Founding Fathers studied the Roman Empire, Ancient Greece, Slovenia, Sweden, and the European Systems that had developed in the aftermath of the Fall of the Roman Empire. When it came to Greece and Rome the writings of Solon, Polybius, Cato, and Cicero were primary targets.

Despite his absence from the Constitutional Convention, Thomas Jefferson had a significant role in the installation of liberty in America and the formation of the Constitution of the United States. While George Washington served as the military sword and executive guide to our system of liberty, Patrick Henry served as liberty's greatest vocal advocate, and Thomas Paine provided the catalyst for action with his pamphlet "Common Sense", it was Thomas Jefferson who served as liberty's scribe and author when it came to the Declaration of Independence, and its consultant through correspondence when it came to the Constitution. In many ways Jefferson confirmed the phrase, "the pen is mightier than the sword."

Jefferson's radical, yet sophisticated, vision of liberty was presented with an eloquence that only he could deliver. He drew from the Saxon and Christian belief that through divine dispensation we all have natural rights. The definition of "Created equal" means an equal distribution of all of the rights provided by the Creator; all human beings are equally entitled to liberty because God gave us each all of our natural rights He commanded were due to us.

All laws that do not preserve liberty, Jefferson argued, are illegitimate. Whenever liberty is not provided by law then the people have a right to rebel. When the rights of the people are not being secured by government, then rebellion against that government is not insurrection, it is a corrective action that the people are duty-bound to carry out. Government, being the primary enemy of liberty and our Natural Rights, must be limited in its power, and corrected when it veers off course.

Jefferson was a student of history, as well as a staunch observer of the struggles during his lifetime. He recognized from practical experience human nature, and the cycles of crisis, tyranny, and liberty.

As a writer, he was gifted. Jefferson drafted more reports, resolutions,

legislation, and related official documents than any other Founding Father. Most important, Jefferson wrote letters. He likely wrote more letters than any of his contemporaries. And, when Jefferson wrote a letter, it was no

small affair. Most of his letters have

survived the ravages of history, around 18,000 are known and still available to

read. He corresponded with just about every

major character who participated in the founding of America as an independent

Union; James Madison, Thomas Paine, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, John Taylor,

Sir William Johnson, James Monroe, Patrick Henry, Matthew Lyon, Marquis de

Lafayette, George Mason, Jean-Baptiste Say, Madame de Stael, and George

Washington; to name a few.

He was reserved in his manner and served as a steadfast friend. He and James Madison enjoyed a friendship that lasted half a century. Jefferson was diplomatic in his dealings with others, using tact that enabled him to maintain relationships even with the most difficult of personalities. John Adams, whom he battled with for a while during the period in which Adams was following Hamilton's lead, commended Jefferson for his “friendly warmth that is natural and habitual to you.”

Jefferson was fairly tall, about six feet two inches, thin, with reddish hair and hazel eyes, and a freckled complexion that helped him stand apart. Early on he cared deeply about his appearance, complimented for being a snappy dresser; but as he trudged along in age he neglected his appearance. His gray hair in his latter days flopped around his head, and during his presidency, it has been reported that he greeted morning visitors in worn slippers and a worn coat.

Jefferson was among the top intellectuals of his day, which is saying something considering the intellectual giants who surrounded him. His ideas formed the Declaration of Independence, guided the early government under the Articles of Confederation, and molded the Constitution of the United States. Even after the end of his two terms as President of the United States, his ideas dominated U.S. government policy. Revered as the “Sage of Monticello” his part in the story of America, which was largely the first fifty years of the country's existence, is an integral part of the founding of our republic and the preservation of liberty.

While those who support the foundation of the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God when it comes to the American System look favorably upon Jefferson's exploits, statists who call for a consolidation of power in the federal government, and a firm union that disallows secession or State oversight regarding the operations of the federal government, struggle with Jefferson's "right-wing" mentality. Followers of Alexander Hamilton's statism, John Marshall's version of federal supremacy, and the top-down Jacksonian Democrats who called for democracy and a stronger executive branch challenged Jefferson's rhetoric regarding a republican form of government. Abraham Lincoln's claim that the United States is a firm union, and his willingness to sacrifice the lives of over 600,000 people to preserve the Union through military force, turned public opinion against Jefferson at the time. Jefferson argued that States had the right to secession and independence. The Lincoln Republicans, and later the politicians of the "Progressive Era," imagined that every problem could be fixed by giving the federal government more power. President Theodore Roosevelt once indicated that his actions as President were not unconstitutional because they were “not expressly prohibited by the Constitution,” a view of federal powers that’s the opposite of the original intent of the Enumeration Doctrine. Teddy Roosevelt also scorned Jefferson for being a “scholarly, timid, and shifting doctrinaire.” He, in turn, praised big government-minded Alexander Hamilton for his work towards increasing government power.

The bicentennial of Jefferson’s birth in 1943 changed the public's perception of the author of American independence. In a sense, the advent of his two-hundredth birthday gave the author of the Declaration of Independence and the third President of the United States a kind of renaissance. The renewed interest in Jefferson's role in the American Revolution, Declaration of Independence, and the dawn of the Constitutional Republic led to the construction of the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C., emblazoned with his stirring oath: “I have sworn upon the altar of God eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man.”

As Cultural Marxism oozed through the crevices of American Society the call for bigger government made a comeback during the 1960s, providing an excuse to attack Jefferson, again.

Some historians revived false Hamiltonian charges that Jefferson fathered children with his young slave, Sally Hemings. In the 1990s the accusation was even a headline in the New York Times. DNA evidence revealed that while a Jefferson did indeed father children with Sally Hemings, it was not Thomas. Instead, according to the DNA evidence, his brother Randolph likely performed the deed.

Despite evidence to the contrary, the falsehood that Thomas Jefferson

was mingling sexually with his slave girls continues to be a primary jab by

leftwing, Hamiltonians of modern-day America.

Current purveyors of Critical Race Theory are demanding reparations for the progeny of black slaves. States like California have already put a plan for reparations into action. The general public has been pelted with claims that America suffers from institutionalized racism, and the fact that Jefferson owned slaves means to them that he didn't necessarily live up to his expressed ideals, making him a fraud, and the ideals he stood for were flawed and unacceptable.

Though Jefferson did indeed have personal failings, such shortcomings do not invalidate the philosophy of liberty he championed. As the Bible so aptly points out, "he who is without sin cast the first stone," John 8:7. All humans on every side of every political debate suffer from personal failings. Human Nature is flawed at its core. "For all have sinned, and come short of the glory of God," Romans 3:23. Therefore, the merit of the ideas developed by the Founding Fathers must not be dismissed as a result. If personal shortcomings were a factor in the validity of the founding principles championed by the Founding Fathers, then every one of Jefferson’s contemporaries and adversaries, past and present, would need to be dismissed, and each and every one of them would cancel each other out.

Jefferson was an avid reader, and among the titles of books that would influence his understanding of liberty: John Locke’s Two Treatises on Government, Adam Ferguson’s An Essay on the History of Civil Society, and Baron de Montesquieu’s complete works were paramount. His library would eventually exceed 6,000 volumes. One wonders if the early bubblings of the phrase, "Readers are Leaders" came from Jefferson's renowned and celebrated reading habits.

Jefferson attended college, studying at William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia for two years. He then read law for the next five years under George Wythe. Judge Wythe, considered to be a distinguished jurist, would later become the first professor of law at William & Mary in 1779. It was in Williamsburg that Jefferson also first became politically involved. The location at the time put him in the thick of things politically, for not only was Williamsburg the capital of Virginia, but the Commonwealth of Virginia was the largest and richest colony of the thirteen. He gained the Virginia bar in 1768, began to practice law in 1769, and then later that same year was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses. He served until 1775, aligning himself with anti-British groups during his time in office.

In 1774, Jefferson wrote his first published work, a 23-page pamphlet called A Summary View of the Rights of British America. The work was a legal brief boldly declaring that Parliament didn’t have the right to rule the colonies. The work established Jefferson as a man who had a way with words, and a man that was willing to stand firm against British tyranny.

In March 1775 Jefferson was named a delegate to the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia. He got to know John Adams, Samuel Adams, and Benjamin Franklin while serving in the Continental Congress. John Adams remarked about his observations regarding Jefferson, “Writings of his were banded about, remarkable for their peculiar felicity of expression…. [Jefferson] was so prompt, frank, explicit and decisive upon committees and in conversation … that he soon seized upon my heart.”

June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee called for the Continental Congress to adopt his resolution for independence. A committee of five was created, combining the great minds of Jefferson, Franklin, John Adams, Roger Sherman, and Robert R. Livingston to prepare a document announcing and justifying independence.

Thirty-three-year-old Jefferson drafted the Declaration of Independence on the second floor of a Philadelphia home. He wrote in an armchair pulled up to a dining table, spending about seventeen days writing the Declaration of Independence.

Mostly a legal brief listing a succession of complaints against England, Jefferson also penned that revolution wasn’t to be undertaken lightly. That said, Jefferson directed America’s case for independence against King George III rather than Parliament, providing a philosophical justification for the conflict the colonists were engaged in against the British army.

The language of the Declaration of Independence not only united the colonists in their fight but became an inspiration not only for every American but for those in the world who also desired the Blessings of Liberty.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; that whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or abolish it, and to institute new government, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness.”

Jefferson’s call for independence was later explained as meaning “to place before mankind the common sense of the subject, in terms so plain and firm as to command their assent, and to justify ourselves in the independent stand we are compelled to take. Neither aiming at originality of principle or sentiment, nor yet copied from any particular and previous writing, it was intended to be an expression of the American mind, and to give to that expression the proper tone and spirit called for by the occasion.”

While Jefferson’s 168-word attack on George III for not outlawing the slave trade was removed from the document, the remainder became the congressionally approved Declaration of Independence, dated July 4, 1776. On July 19, fifty-six men officially signed the document, which became the official launch of liberty in America.

About 75 years before the birth of Christ, the Roman Republic had reached its zenith. Rome was the lone superpower in the world. What began as a kingdom, and then a republic, equipped with a system of representation, was becoming something the founders of the Roman Republic never intended. The leadership was wealthy beyond imagination, and had attained incredible political power. The rulers had become suspicious of everyone, intolerant of opposition, indifferent to the demands of the middle class, and considered the Roman Constitution, embodied physically in the Twelve Tables of Law, which was designed to curb their ambitions and serve as an impediment to their aims, archaic and out of date.

Marcus Tullius Cicero was but a young man, a student of law under old Scaevola, the eminent lawyer of his day. Cicero, whose writings many centuries later would be studied by men like Thomas Jefferson, was disillusioned. Caesar, in complete disregard for the rule of law, had by force of arms, guile and trickery, used his military to dominate the world.

Society, like the leaders, were tossing aside cultural standards set by the early Romans. The citizens were no longer worried about defending their rights, and had instead learned to live on the gifts from the treasury the politicians had offered them for their votes. They were fat, immoral, careless, and happy to live on the government's offerings, which had been taken by bureaucratic chicanery from substantial men of business.

One such man, wealthy, but wronged by politicians that coveted his wealth, came to Cicero for representation. Cicero built his case, and presented it, but the judges were not responding in the way Cicero had expected. The law was being set aside, believed Cicero. The jurists of his day were no longer following the rule of law, and instead ruled based on the demands of the political elite, and society’s lusts and desires.

Cicero plead his client's defense against confiscatory taxation, saying "we are taxed in our bread and our wine, in our incomes and our investments, on our land and on our property, not only for base creatures who do not deserve the name of man, but for foreign nations, for complacent nations who will bow to us and accept our largesse and promise us to assist in the keeping of the peace - these mendicant nations who will destroy us when we show a moment of weakness or our treasury is bare. We are taxed to maintain legions on their soil, in the name of law and order and the Pax Romana, a document which will fall into dust when it pleases our allies and our vassals. We keep them in precarious balance only with our gold. Is the heart-blood of our nation worth these? Shall one Italian be sacrificed for Britain, for Gaul, for Egypt, for India, even for Greece, and a score of other nations? Were they bound to us with ties of love, they would not ask our gold. They would ask only our laws. They take our very flesh, and they hate and despise us. And who shall say we are worthy of more?"

Cicero did not save his client. But he did live to argue the cause of honest government and to talk with Sulla, the Dictator (Senate appointed leader), about integrity and fair dealing. Sulla had little faith in the people. He believed them too deeply interested in their own welfare to concern themselves, too timid to stand up for their rights. He told Cicero the middle class, the lawyers, the physicians, the bankers, and the merchants would make no sacrifices. He said none of your lawyers will challenge the lawmakers and cry to them, "This is unconstitutional, an affront to a free people, and it must not pass!" Cicero asked "Will one of these, your own, lift his eyes from his ledgers long enough to scan the Twelve Tables of Roman Law, and then expose those who violate them and help to remove them from power, even if it costs their lives? These fat men. Will six of them in this city, disregarding personal safety, rise up from their offices and stand in the Forum, and tell the people the inevitable fate of Rome unless they return to virtue and thrift and drive from the Senate the evil men who have corrupted them for the power they have to bestow?"

Rome continued to decay. The liberties of the people were being trampled upon in the name of emergencies (crisis), or they were relinquished voluntarily so as to be awarded government benefits.

Cicero, in his Second Oration before the Senate, provided, "Too long have we said to ourselves 'intolerance of another's politics is barbarous and not to be countenanced in a civilized country. Are we not free? Shall a man be denied his right to speak under the law which established that right?' I tell you that freedom does not mean the freedom to exploit law in order to destroy it! It is not freedom which permits the Trojan Horse to be wheeled within the gates. . . He who is not for Rome and Roman Law and Roman liberty is against Rome. He who espouses tyranny and oppression and the old dead despotisms is against Rome. He who plots against established authority and incites the populace to violence is against Rome. He cannot ride two horses at the same time. We cannot be for lawful ordinances and for an alien conspiracy at one and the same moment. Though liberty is established by law, we must be vigilant, for liberty to enslave us is always present under that very liberty. Our Constitution speaks of the 'general welfare of the people.' Under that phrase all sorts of excesses can be employed by lusting tyrants to make us bondsmen."

Years later Cicero appeared before the Senate again.

He said "The Senate, in truth, has no right to censure me for anything, for I did but my duty and exposed traitors and treason against the State. If that is a crime, then I am indeed a criminal."

Crassus, Caesar and Pompey were in the hall listening to Cicero, but turned away to reject his words. He said to them, "You have succeeded against me. Be it as you will. I will depart."

He then told the Senate: "For this day's work, lords, you have encouraged treason and opened the prison doors to free the traitors. A nation can survive its fools, and even the ambitious. But it cannot survive treason from within. An enemy at the gates is less formidable, for he is known and he carries his banners openly against the city. But the traitor moves among those within the gates freely, his sly whispers rustling through all the alleys, heard in the very halls of government itself. For the traitor appears no traitor; he speaks in the accents familiar to his victims, and he wears their face and their garments, and he appeals to the baseness that lies deep in the hearts of all men. He rots the soul of a nation; he works secretly and unknown in the night to undermine the pillars of a city; he infects the body politic so that it can no longer resist. A murderer is less to be feared. The traitor is the carrier of the plague. You have unbarred the gates of Rome to him."

Cicero was exiled from Rome for his words. From outside of Rome he continued to plead the cause of honest government. The people were not concerned. They were satisfied living a mediocre life on the public dole. His friends were also satisfied, and did not wish to make waves. They were lawyers, doctors, and businessmen, and they told him, "We do not meddle in politics. Rome is prosperous and at peace. We have our villas in Caprae, our racing vessels, our houses, our servants, our pretty mistresses, and our comfort and treasures. We implore you, Cicero, do not disturb us with your lamentations of disaster. Rome is on the march to the mighty society, for all Romans."

Cicero was in despair. He began to write his book De Legibus, but Atticus, his publisher, asked, "But who will read it? Romans care nothing for law any longer, their bellies are too full."

Cicero, however, was not completely unheard. Brutus, the long-time sycophant of the ambitious Caesar, went to Cicero with his plea that something be done to save the nation. He confessed his error, he said he had believed in Caesar. Brutus believed that Caesar would restore the republic. Caesar had betrayed his trust.

Cicero replied, "Do not blame Caesar, blame the people of Rome who have so enthusiastically acclaimed and adored him and rejoiced in their loss of freedom and danced in his path and gave him triumphal processions and laughed delightedly at his licentiousness and thought it very superior of him to acquire vast amounts of gold illicitly. Blame the people who hail him when he speaks in the Forum of the 'new, wonderful good society' which shall now be Rome's, interpreted to mean 'more money, more ease, more security, more living fatly at the expense of the industrious.' Julius was always an ambitious villain, but he is only one man."

In the end, Cicero was unable to save the Roman Republic, and the system of liberty that accompanied Rome’s republic before Caesar changed it into a tyranny that wore the face of a democracy promising peace, safety, and the common good based on the best of intentions.

Despite Rome moving from a republic to a tyranny that suffered under a succession of Caesars, his work was not all for nothing. Nearly 1,800 years later Thomas Jefferson read Cicero’s writings and built his case for liberty partially based on what he had learned from Cicero. Jefferson assisted in establishing liberty for America, and Cicero assisted also in establishing liberty through what he wrote during a time in which he was fighting to save liberty in his own doomed civilization.

Which brings us to the current situation here in the first quarter of the twenty-first century. Are we “Jefferson” who had a hand in preserving liberty, or are we Cicero, whose work to save liberty failed during his time, but was an integral part in establishing liberty in America. In short, either we will succeed in preserving liberty like Jefferson, or our work will become the inspiration for a future generation as they work to resurrect liberty like it was for Cicero. Either way, our fight is admirable, and worthy.

-- Political Pistachio Conservative News and Commentary

No comments:

Post a Comment